When I started seminary, I hadn’t had too much personal experience with anti-Judaism or anti-Semitism. My father is Jewish and my mother is Presbyterian. Growing up, Dad exposed us to some Jewish practice and holidays, but mostly my brother and I were raised in the church. We attended worship every Sunday, were baptized and confirmed. Sure, there had been the odd, isolated incident. There was that time when I was a TA while getting my Masters in Social Work when a student wrote this sentence in a paper about the professor: “even though he Jewish, he still think it good to help people.” Grammar aside, this sentence warranted a much longer conversation on a number of topics.

Still, I found myself unprepared for the first meeting of church history class at seminary. The professors who taught the class had decided to begin with a brief overview of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus in order to launch into the founding of the church and beyond. As good teachers do, they narrated and asked questions to engage the class. And then one of the professors asked the class, “who killed Jesus?” The class answered as a whole, but not as a whole. Maybe 70% of the room said, “the Romans” and 30% said, “the Jews.” I bristled in disbelief. What was this? What was happening? Did that just happen? Did I imagine it? I did not imagine it. The professor seemed to also be taken aback and she reiterated, something like, “according to the precise biblical narrative, who killed Jesus?” Then, maybe 90% of the room said, “the Romans,” but 10% said, the, “the Jews” again. They were somewhere behind me – I couldn’t see their faces.

“The Jews killed Jesus”

I spent the rest of the class frozen. What did this mean? Where had I moved? Would I be safe here? Everyone knew, or shortly came to know, about my Jewish heritage. I had spent a lifetime studying the Holocaust, the Weimar era, the rise of the Nazis, how they won hearts and minds, how people rationalized their support or acceptance of the Nazis, how they tried to erase their involvement after the fact, how the world often tried to forget the roots and the pervasiveness of anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism before during and after the Holocaust.

I was frozen so I waited after class to talk to the professor, but I needed to wait until everyone else was gone. This meant that I overheard the group ahead of me. Apparently some of them had said, “the Jews.” If I remember correctly, it was mostly middle-aged women in this group. One sentence has stuck with me. One of them said, “even if it made sense to blame every Jewish person who was alive at the time, it wouldn’t make sense to blame every Jew forever for the death of Jesus.” This was said like it was a revelation, an aha moment, something that had never occurred to them prior to this very conversation. There were smiling nods of agreement across that group. I felt sick, but said nothing. I spoke to the professor, but I don’t remember what she said or what I said.

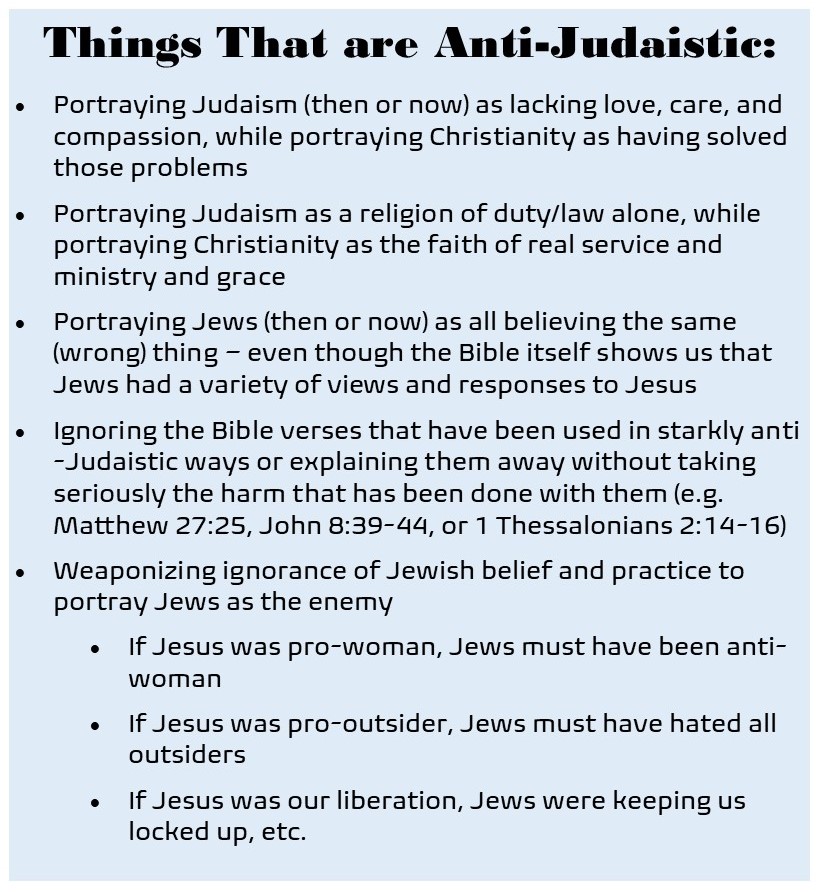

I spent much of the rest of seminary educating myself about Judaism in Jesus’s day and in the present so that I could speak out, so that I would know how to respond. I did not want to be blindsided any more, but to be prepared to challenge the anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism that lingers in Christian theology. We don’t talk about it or think about it too often. I’m sure I’ve never met a Christian who would claim to be anti-Jewish or anti-Semitic. They would be the first to decry that kind of hatred. But I cannot tell you how commonly I hear anti-Jewish statements inter-mingled into Christian theology. It’s so basic to how our beliefs have been formed and shaped for thousands of years that we often cannot even tell when we’re espousing it.

So, I naively thought, if I could just make people aware of it, they would hear, learn, and seek to do better. But this is not how it works. You cannot just tell people where they have said or done things that are causing harm. You have to take them aside in private. You have to say nice, glowing, complimentary things about how you know they’re a good person and how they don’t mean any harm and you’re not mad at them personally, BUT. Only then, if you’re lucky, can you tell people something that they have said or done with the remotest chance that they will actually hear it. Otherwise, they tend to shut down from the get-go. I gotta tell you – this whole process is exhausting, draining, and far, far too complicated.

What baffles me the most about it is that we are Christians, right? As Presbyterians, we’re big on the “grace sandwich” – first God’s grace, then the awareness of our sin, and then the hope and promise of grace/mercy/redemption/salvation. Grace is first and last because we believe sin has been conquered and so we are saved from it.

“All have Sinned and Fall Short of the Glory of God”

So, if we really, truly, seriously believe with Romans 3:23 that, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” why, oh why, are we the hardest people to challenge? When someone takes the great personal risk to come forward and tell us – you have done wrong, you have hurt me – shouldn’t we be the easiest people to talk with, to work with, to reconcile with, to heal and change and do better?

In Luke 17:3, Jesus tells us, “be on your guard! If another disciple sins, you must rebuke the offender.” Jesus didn’t tell us that we would never sin again if we believed in his name. He said that we absolutely would sin and that part of our responsibility as a community of faith is to hold one another accountable. This is distinct from “judge not” – it’s not about being judgmental, but about being able to be honest with one another so that we may grow together and be more faithful together. If one of us sins, we have a responsibility to rebuke one another. But this word “rebuke” doesn’t mean to yell and scream and denigrate someone. It doesn’t mean to lift oneself up as the arbiter of good and evil, claiming power over each other. The word is epitimao. Literally, it means “to set a proper value.” So, it could mean to honor someone if that’s what the context warrants. More commonly, it talks of rendering what is due. It means to show someone what their behavior is, what impacts it has, where it strays from our faith, and where improvement can be made. Quite often, the word is used in the sense of warning someone about where the path they’re on is heading.

Continuing in verse 3, Jesus tells us, “you must rebuke the offender, and if there is repentance, you must forgive.” This word repentance, metanoeo, is often discussed in commentaries. Whereas the word “repent” has its roots in being sorry for what we have done, the Greek is more active and involved. Metanoeo is not about merely feeling bad; it literally means, “to change how one thinks.” It is to be so impacted by realization of what you have done wrong, that your entire way of understanding your actions, motivations, and beliefs shift. Metanoeo is a far greater transformation than simply feeling guilty and wanting to make nice. We can see, then, that following true repentance as understood biblically, it is far easier for the wronged party to come to a place of reconciliation and forgiveness.

Right now, a lot of people are being harmed and a lot of people are putting themselves out there to call out others for that which is harming them. Many people of color are highlighting racism where they have experienced it personally and in society. People with disability are trying to get us to see how ableism has impacted them. Jews are trying to show us anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism, people of different genders and sexualities are trying to show us what threatens their lives, veterans are trying to show us how they are disparaged and lost in the system. The list of people who are being harmed right now seems endless.

“Be Teachable”

Many of us have gotten used to only seeing and understanding what has come most naturally from our own perspective. Suddenly, in the midst of a pandemic, there are all of these voices trying to rebuke the nation and us individually on so many fronts. As Christians, as sinners, as redeemed believers in the grace of Jesus Christ, it is our responsibility to listen with humility. It is our responsibility to be teachable, to be reformable, to seek to learn and to grow. Our knee-jerk reactions of – that’s not what I/they meant or you don’t know my heart – those do not serve our faith or our communities. Our good intentions do not undo the impact of our words and deeds. Constantly coming to our own defense, rejecting any information that challenges us or calls us out as sinners – that’s not coming from our faith, that’s coming from our pride. I know it’s not easy. I know we don’t like it. It’s much more gratifying to hold others accountable than it is for someone else to hold us accountable. But, folks, being hard to rebuke is not part of our calling and it’s an area where we need to do better.

Practice these Phrases

- I’m sorry (not “I’m sorry, but let me defend myself.” Just I’m sorry).

- I didn’t realize I hurt you, but can you help me understand?

- You don’t owe me an education about this – I will take the time to study it myself.

Ecclesiastes 4 tells us that it is better to have a friend – to be together with another. “For if they fall, one will lift up the other, but woe to the one who is alone and falls and does not have another to help” (Ecc 4:10).

The more pride we have, the more we alienate our friends who could be there to try to help lift us up. Why should we stay stuck on the ground of ignorance, prejudice, and misinformation? Rather, in faith, be someone that can be lifted up by another child of God and see what a difference it makes.

Image Credit: “Jesus Cures the Man Born Blind” by Jesus MAFA, a community in Cameroon, 1973.